Not a single window remained unscathed in the port explosion of August 4th, and that includes the façade's colorful stained glass, which turned into dust due to the force of the blast.

In March 2021, we received the hand-blown glass which will replace the façade’s shattered stained glass windows. These large sheets of red, blue, and yellow glass were generously donated by Saint-Gobain.

Weighing more than two tons, the stained glass we received was produced in Verrerie Saint-Just, located in the French town of Saint-Just Saint-Rambert. Verrerie Saint-Just is the last atelier in France that still makes glass using the traditional glassblowing technique. Most recently, they produced hand-blown glass for the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris, France.

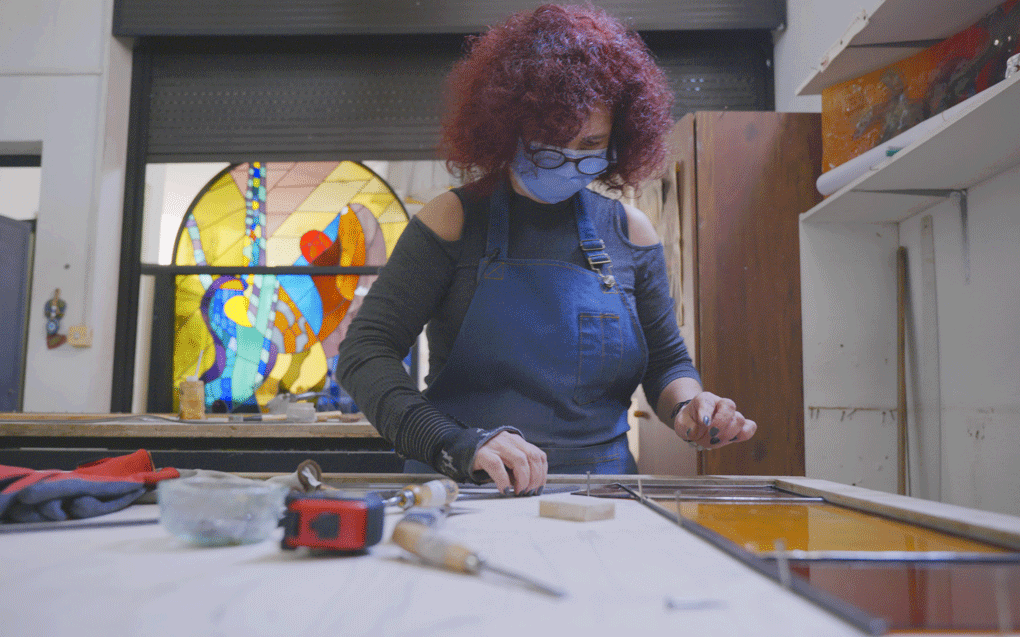

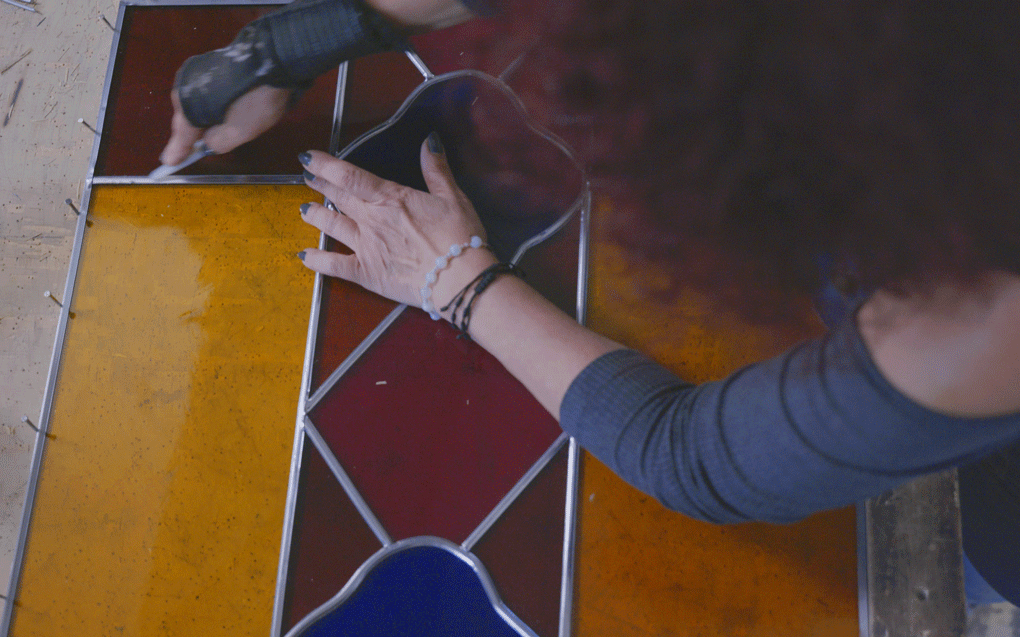

Stained glass artist Maya Husseini is currently working in order to transform these flat sheets of glass into the beautiful stained glass windows that we all remember and love.

As the glass is hand-blown, a single sheet can vary from 2 to 5 mm. Every single one of them is unique.

Maya worked on the Sursock Museum’s façade’s stained glass once before: during the Museum’s latest renovation project, which lasted from 2008 to 2015. For the windows, she followed the exact same design that was originally used in Nicolas Sursock’s lifetime, using archival photographs from the time as a reference.

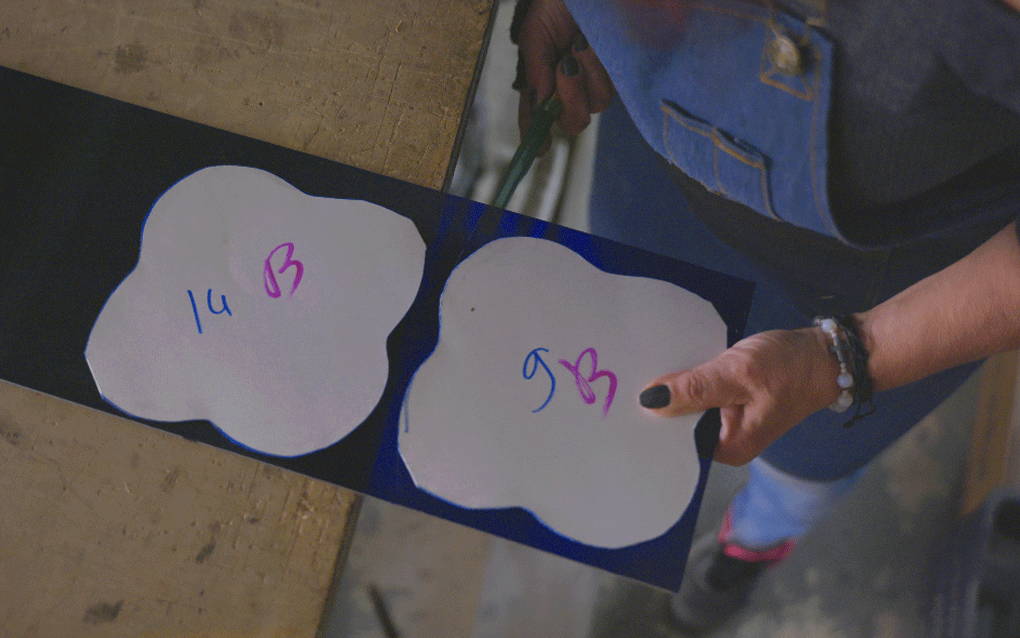

Thankfully, Maya still has all the patterns for the windows from the previous renovation in her own archive. Otherwise, she would have had to redraw them from scratch.

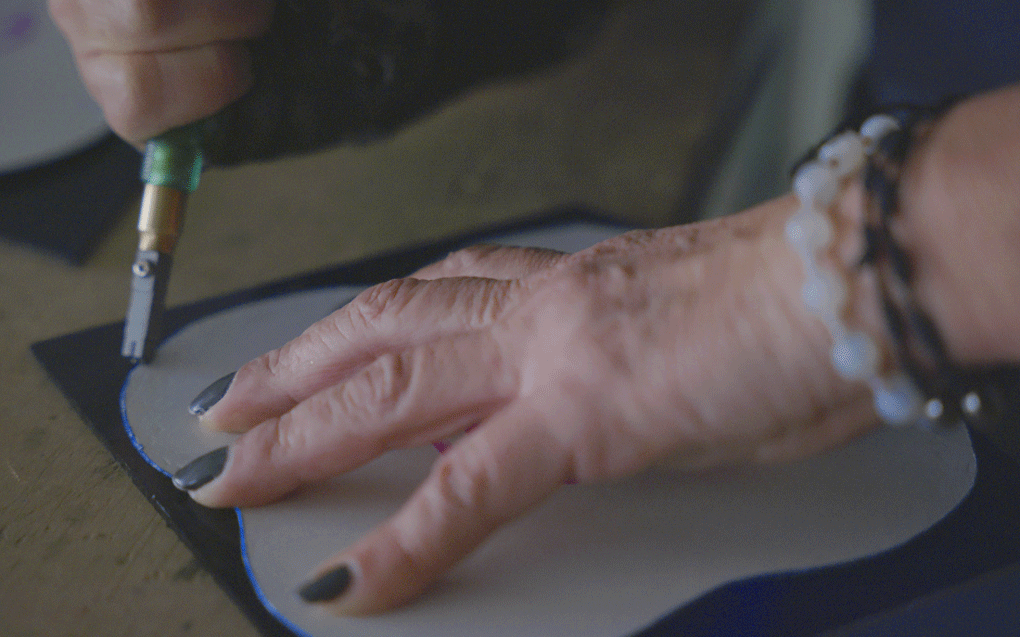

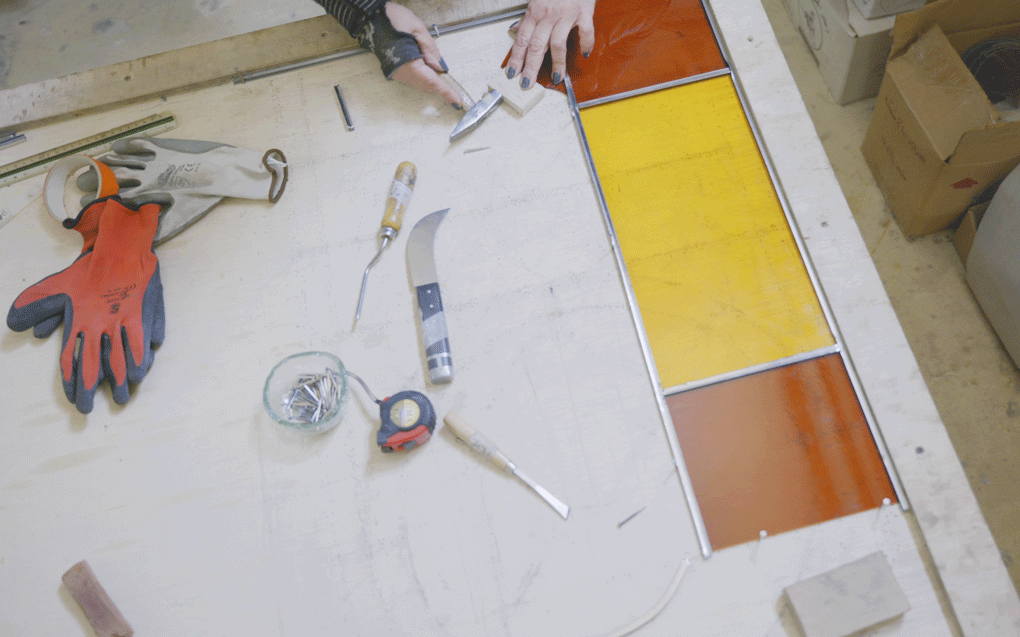

Every window features several shapes: triangles, rectangles, circles, not to mention the Museum’s signature shape, the rosace. Maya cuts the sheets of glass into each one of these shapes, creating a montage for the full window, before finally securing the newly-shaped structure with led, welding the intersections.

The last step is to rub putty (mastic) into the glass, letting it sit, then removing the mastic with wood powder. This process solidifies the entire structure, especially at the junctions of the different shapes.

“The stained glass, the tools I use in my work, everything comes from abroad,” she says. “But the labor that is poured into this craft comes from here.”